Not all bad: How “good” viruses boost your well-being By Virgilio Marin for Natural Medicine

Though viruses are known for causing disease, not all of them are harmful. In fact, some viruses in your body are important for your overall health and may even help eliminate infections. Called “bacteriophages,” these “good” viruses are natural antibiotics that pack a mean punch against bad bacteria.

What are bacteriophages?

The community of viruses inside your body is called the “virome.” The virome makes up part of the total population of microorganisms living inside your body, which is collectively called the “human microbiome.” Researchers also use the term in reference to the sum of the genetic material of these microorganisms.

The virome is considered to be the largest, most diverse and most dynamic part of the human microbiome. It emerges a week after birth, at which time about 100 million viruses can be found in a gram of a baby’s poop. Communities of viruses are commonly found on mucosal surfaces, such as the lining of your gut and the insides of your nose. In general, however, the majority of them are found in your gut and are made up of bacteriophages.

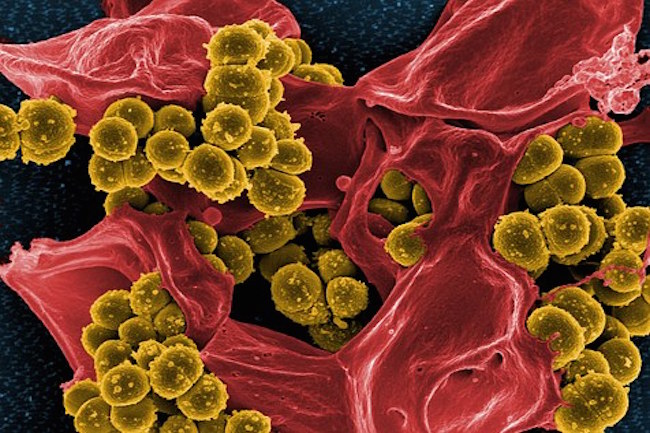

The term bacteriophage, which is Greek for “bacteria eater,” refers to a virus that infects a bacterial cell and reproduces inside of it. Bacteriophages thrive wherever there are bacteria, and they are also very adept at destroying these pathogens.

As early as the 1920s, researchers have been investigating whether bacteriophages can be used to treat bacterial infections. Their findings show that bacteriophage therapy is an effective treatment strategy that doesn’t cause any adverse effects. Though interest in bacteriophage therapy has waned since the advent of antibiotics, advancements in technology, the threat posed by antibiotic resistance and the advantages of this therapy have drawn attention back to it in recent years.

One advantage of bacteriophage therapy is its high specificity. Bacteriophages target a narrow range of strains within the same bacterial species, which is ideal because it spares the “good” bacteria in the gut. Antibiotics, on the other hand, wipe out a wide spectrum of bacterial species, which can throw your gut microbiome out of balance. (Related: Natural bacteria-killing viruses in the bladder may prove more effective at clearing UTIs than antibiotics.)

Real-life cases treated using bacteriophage therapy

Phage therapy is not yet approved for human use in the United States, and research is still needed to confirm its safety. In 2016, however, the University of California San Diego Health (UC San Diego Health) used phage therapy under emergency use approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat a deadly infection caused by the multidrug-resistant bacteria Acinetobacter baumannii.

The patient, psychiatry professor Tom Patterson, received an intravenous phage cocktail that specifically targeted A. baumannii. He began improving almost immediately and eventually emerged from a months-long coma. Patterson has since returned to work after making a full recovery.

Patterson is the first American to undergo intravenous phage therapy. After him, five more patients at UC San Diego Health have been treated with phages, one of whom had a years-long infection that bacteriophage therapy successfully cleared.

Besides medicine, bacteriophages are also used in the food industry to stop bacterial growth in food. Mixtures of phages that are approved by the FDA for this application are added to processed foods to prevent spoilage. Researchers are also exploring the use of phages in cleaning products.

Phages can be thought of as nature’s antibiotics and may be viable alternatives to antibiotic medications. Though more studies on bacteriophages are needed, cases like Patterson’s show that bacteriophage therapy is full of promise.